COYOTE First Aid Kit: What to Do if You Find Feral Kittens

It’s baby cat season in the Bay Area! Here’s our guide on what to do if you encounter a litter of purrfect miniature panthers in your yard.

It’s baby cat season in the Bay Area! Here’s our guide on what to do if you encounter a litter of purrfect miniature panthers in your yard.

This week we've got crafts, crows, and corner pockets.

Once, they were kids walking the hallways of Oakland School for the Arts. Now they're at the Grammys, publishing bestsellers, and performing at the SF Ballet.

Mohammad Gorjestani honors Oscar Grant and other victims of police violence with an interactive exhibit full of birthday messages.

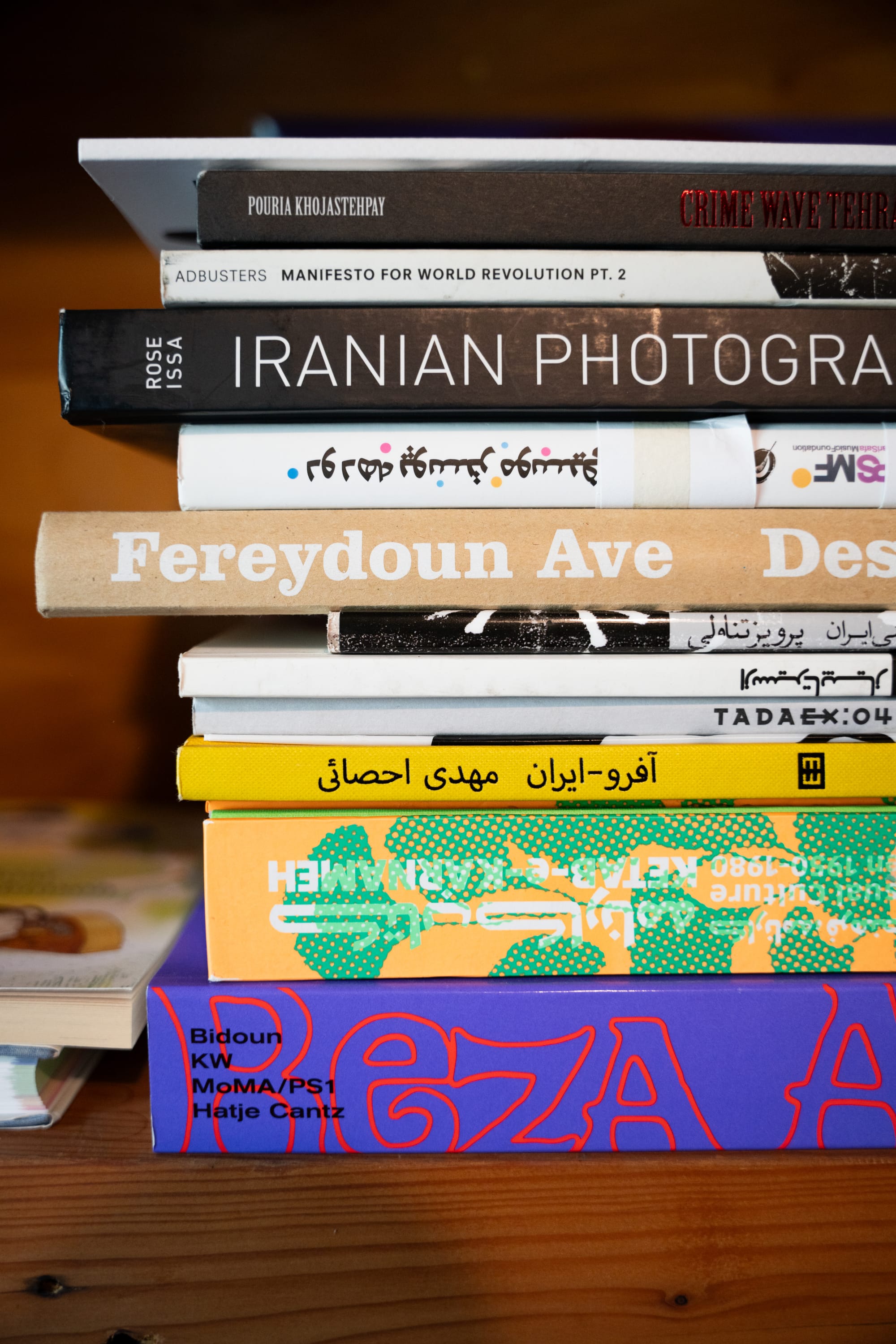

When you walk into Even/Odd Studio — a hidden nook in San Francisco’s Mission District, adorned with a mix of imported Iranian rugs and contemporary Bay Area art depicting sideshows and Iranian sports heroes — the first person to greet you will be the founder, Mohammad Gorjestani.

Rocking a Giants-themed Bip City snapback, he’ll kindly ask you to remove your shoes, offer a warm beverage, then toss you into an unrelenting vortex of ideas: film concepts, international politics, upcoming art exhibits, social justice issues, the latest Bay Area rap mixtapes.

The first-gen Iranian-American filmmaker and photographer immigrated to the USA with his family in 1988, and was raised in the San Jose Gardens, a public housing project. A former wrestler, he’s not one to tiptoe around anything, never yielding ground on his beliefs. His studio has produced a Super Bowl-aired commercial featuring NFL superstar, Saquon Barkley, worked with Snoop Dogg (remember this viral smokeless grill ad?), actor Jeremy Allen White, Megan Thee Stallion and Vince Staples, and has regularly led campaigns for brands like Nike, Cash App, and Beats By Dre.

Mohammad Gorjestani walks through his studio, which is decorated with adorned with Iranian art and trinkets that remind him of home. (Florence Middleton for COYOTE Media Collective)

Beyond the glamorous celebrity projects, Gorjestani is community-driven and down as fuck. His studio’s work portrays the raw-yet-celebratory realities of common people: grieving mothers, the formerly incarcerated, daughters of immigrants. His and Even/Odd's focus often hyper-local: The studio has spotlighted a group of female DJs in the Chulita Vinyl Club and co-founded a media project honoring the late Jeff Adachi, San Francisco’s former public defender, all with an emphasis on everyday struggles and joys.

On Jan. 19 (MLK Day), Gorjestani's Even/Odd and Brooklyn's WORTHLESSSTUDIOS will re-launch Gorjestani's exhibit "1-800 Happy Birthday" at Fort Mason's The Guardsman building. The multi-format project — which started as a website and short film in 2014 — honors victims of police killings by inviting family, friends, and strangers to leave birthday messages on repurposed NYC phone booths. The project recently received $1 million in grants led by the Mellon Foundation and BLM Global Fund, will also appear at the Black Joy Parade in Oakland on Feb. 22 and at the Black Panther Party Museum in February for an installation honoring Oscar Grant, in collaboration with his mother, Wanda Johnson.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Alan Chazaro: You work across audio, visuals, photography, film. What do you think about these labels?

Mohammad Gorjestani: The terms we place on ourselves are used to orient our goals, but internally it’s all a continuing odyssey of understanding who you are. For me, that used to be sports, and now it’s art and film: they’re used in service of unpacking, and coping, and evolving. And that’s very difficult to do in a way that is sustained and balanced and allows for you to be a creative person when it all exists inside of capitalism. But I think Even/Odd Studio is an amalgamation of all that.

AC: Where did you gain that mindset? It takes a lot of courage to live off your art, and to do it authentically. I’ve known a lot of Bay Area-raised people who share that desire to be true to themselves and not sell out for the sake of chasing bigger paychecks.

MG: I had to deprogram my assimilation. I don’t mean that about race and identity, but in the context of what it means to be a filmmaker. There are monolithic aspirations: live in LA or NYC, constantly write screenplays. But what if that system doesn't sit well with your nervous system? When what you want to make doesn't fit the commodity of that traditional market?

Growing up in the Bay, you get really comfortable with your favorite music and art not being popular everywhere. Go 300 miles east, and people are like, I’ve never heard of that. That’s their loss. I’ve never been someone who is chasing an Academy Award. I don’t feel the need to be accepted in places I feel are institutionally corny. That’s honestly just about feeling safe in my own nervous system. I’ve found ways to keep going through short form, then doing some commercial stuff that helps me to do more short form has allowed me to enter long form through a unique path. I don’t need to be at the mercy of another studio. There’s a saying, “make what you know.” But part two is, “I’m comfortable with it being niche and no one caring about it.” That’s a freeing mechanism of going out and doing it, and that’s ironically what people respond to most.

AC: 1-800 Happy Birthday centers the mothers and families of people killed by police. What do their stories mean to you?

MG: I’ve had lots of proximity to grief and the various forms it exists in. Maybe it’s a cultural thing — there’s a lot of imagery from Iran that is intensely emotional and perhaps has tuned me subconsciously — and for me, when Oscar Grant was killed, for example, I was very upset and disturbed. But what really broke me was the first time I saw his mom on the news. I felt this deepness. I imagined it, and it felt unbearable even just trying to approach that feeling. I remember, being in the Bay, being in SF, feeling how disconnected it all felt here, like it was more important elsewhere than it was in our own backyard. Mario Woods, too. Beyonce put his name on a sign at the Super Bowl, but at home, no one knew who [Woods] was.

As a filmmaker, I have creative resources and ability. How can I participate and get others involved? I reached out to Wanda [Johnson] about what she was doing on [her son] Oscar’s birthday. Even though the news cycle had passed, I wanted to capture her cinematically on the other side of her grief journey. Now she’s a leader. That arc wasn’t a news headline: Oscar Grant’s mom is healing and helping the community. It inspired the idea to create a website for people to call and leave messages. I felt like there was meaning in sharing a collection of voice notes with Mario’s mom. She felt supported and loved.

AC: What’s a project you’re currently working on that embodies these different aspirations and goals you have?

MG: From The Mat. It’s a multimodal project – mainly a feature film and a body of photography. It was also a homecoming for me returning to Iran after 36 years and exploring Iranian identity through the sacred sport of wrestling. Going back in the summer of 2024 was probably the most transformative moment of my life.

Growing up how I did, in my generation, our parents were very traumatized by leaving their homeland and never going back. We also have a fairly complex and toxic diaspora, in which a geopolitical context is how you frame yourself and your identity. That all chips away at you, but over time you kind of numb it, and one day, that numbing agent is removed. There’s liberation and pain in equal dosage. [From the Mat] has been the thing that I feel like I need to do so that I can get on the other side of this thing I’m going through.

AC: Have there been other works that have inspired the way you’re approaching it as a filmmaker?

MG: Beau Travail, the Claire Denis film, comes to mind — the form, how it exists in this masculine way. Hale County This Morning, This Evening was also a very important film for me. “Territory” by the Blaze. The film where they put a bunch of cameras on Zinedine Zidane for an entire 90-minute match. It’s about resisting what you think: The pacing is the game. And Tokyo Olympiad. Japan hired its best directors to film the ‘64 Olympics and they treated [sports] like performance art.

In terms of spiritual reference [for Off the Mat] it was just from watching Iranian wrestling. Iranian wrestling media is robust with history and lore. I wanted to make this film because I couldn’t explain Iranian wrestling to anyone. I would watch things on Instagram, YouTube, wherever. Eventually my imagination allowed me to see it through a cinematic lens.

AC: Going back just over a decade, there has been a surge in local filmmakers with major box office productions like Fruitvale Station, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Black Panther, Blindspotting, Freaky Tales, and a handful of others. What has been the root of that renaissance?

MG: There are some things in the ecosystem here that people may not know about like the Kenneth Rainin Foundation and SFFILM, which was formerly the San Francisco Film Society. Those became hubs to facilitate projects that we know about today. I can think of so many projects that came out of those various cohorts. Ryan [Coogler] and Fruitvale Station; Ryan had evolved and developed so much of that project through SFFILM. Boots Riley, Sorry to Bother You. Joe Talbot with Last Black Man.

The project that kind of started the [film renaissance] wave here was Barry Jenkins’ first film, Medicine for Melancholy, in 2008. It captured a version of San Francisco that up to that point, in my opinion, hadn’t really been captured. It was a low-budget indie film about a very specific experience here. The continuation of that is films like Crip Camp, The Waiting Room, and more well-known ones, like Earth Mama by Savannah Leaf. The Bay Area is the epicenter, and a microcosm, of America.

AC: Is that energy still present in today’s film scene? And what are some of the challenges of maintaining that here?

MG: You can be on Market between 10th and 8th streets, walking by people at the very bottom of the class strata, folks who are not doing well, and odds are, you’re also walking by a million-dollar person or billion-dollar company. Meanwhile, you got people asking you for money, all stacked on top of each other.

This is a critical time. We’re kind of having this moment of a San Francisco revival, of the city coming back, right? But for who? Who gets left out? That’s why art, films, are so important. They put the elephant in the room. They address inconvenient truths. [Authorities] are trying to shut down sideshows in SF. They want to extract what they want, and censor the people who made the culture that they’ve exploited. It’s goofy. It’s why I’m hellbent on keeping my practice and studio in this city.

AC: Final words for other Bay Area artists?

MC: If there’s one thing I can tell my own community — I’m a die-hard progressive community kid — but we gotta make aesthetics. You gotta make sure your shit looks dope. Your message has to be fly. That’s the reality.

Alan Chazaro is a traveling Bay Area dad and writer currently based in Veracruz, Mexico. His forthcoming poetry collection, These Spaceships Weren't Built For Us, will be published with Tia Chucha Press in 2026.

View articles